What is Luck?

At one point in life I got interested in the concept of luck. It was the one thing I wish more speakers in business school attributed at least part of their success to. It was also something that everyone seemed to have a strong opinion of, usually with very little justification (let alone a good framework for understanding it or compelling, objective data).

In my reflections I’ve arrived at the following tenets

Luck happens to everyone – it’s the naturally occurring variance of outcomes

Luck is an important factor that affects outcomes – usually not what people give it credit for. Very likely (because of the Fundamental Attribution Error), people overestimate the impact of bad luck, and underestimate the impact of good luck

Luck is subjective and nuanced – it can be good or bad depending on the circumstance, but also depending on the perspective (someone’s good luck may be another’s bad luck), and even controlling for the circumstance and the perspective, it may look different depending on the subject’s mindset and the time horizon being considered (bad luck being rejected from a university may lead to good luck coming up with a brilliant invention)

We cannot control luck

However, we can control how we react to luck, and by reacting well, we can significantly improve our outcomes

I tried to bring that last point home by building a “luck simulator”. The simulator uses randomness to chart some outcome. For simplicity, let’s assume the outcome can take a range of values from very positive to very negative, and time proceeds in quanta.

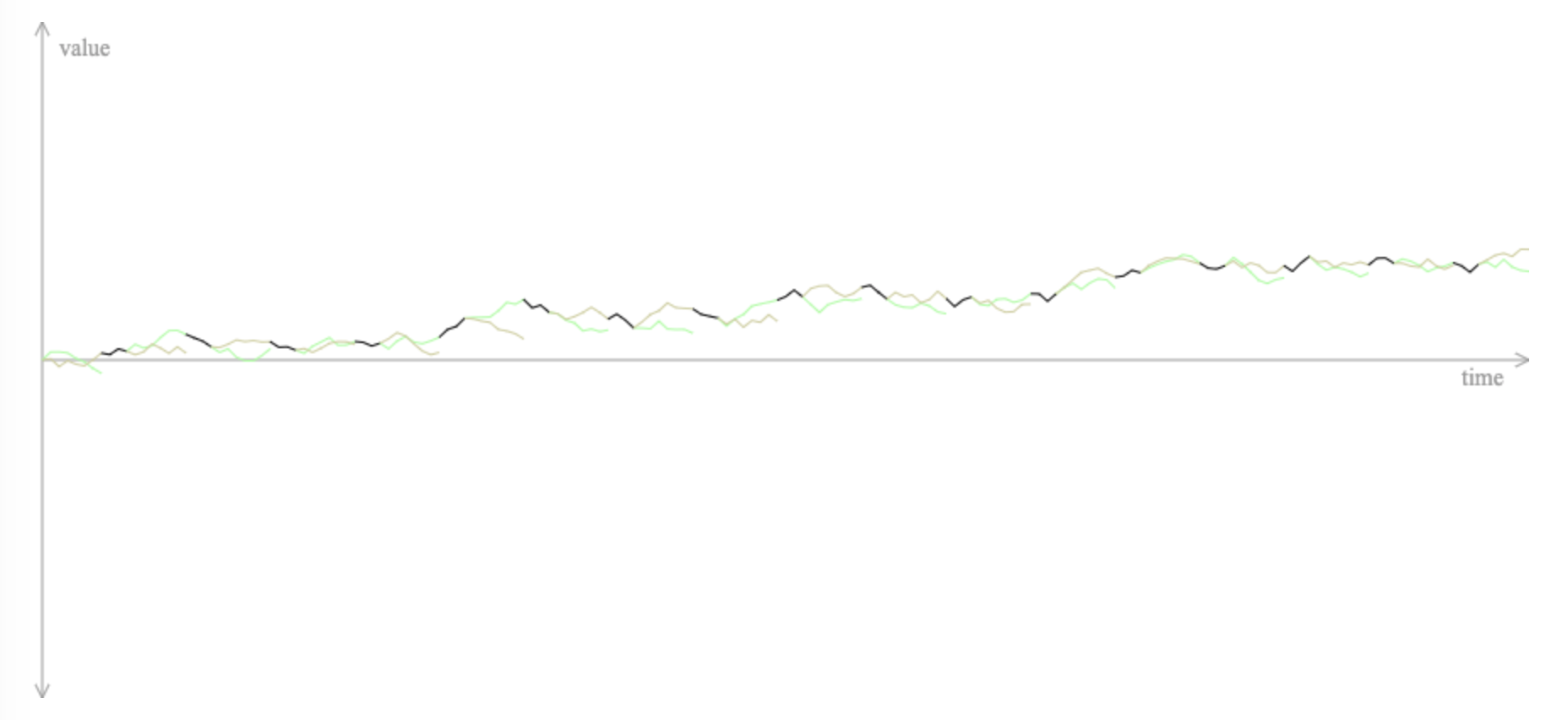

“Pure luck” is just a random walk, no bias either way. You may end up with something like this:

What “pure luck” could look like.

However, we can react to luck well by exposing ourselves to more events, each of which has a component of luck, and choosing the path that gives us a better outcome. Let’s imagine a scenario where for 1/3 of the time we let “pure luck” take course, but for the remainder of the time we explore two paths in parallel and at the end of each period, pick the better outcome. This creates a biased random walk that might look like this:

Explore two alternate paths, two-thirds of the time.

Finally, imagine an even more drastic version of such selection, where we always explore four paths in parallel and pick the best one every, say, six steps. As you can imagine, this is biased significantly upwards:

Explore four paths at a time, pick one every six steps. We run out of space on the Y axis…

(The expected value of each strategy is left as an exercise for the reader. Hint: EV(A)=0)

The takeaway, at least for me, is to harness luck – explore multiple paths in strategic moments, and pursue the ones that look promising. With advanced modeling we could extend this to the idea of time horizons as well. In the meantime, you can play with the simulator here: